In a lab in Porton Down, scientists are growing human organs on tiny cassette-like chips to help accelerate the development of new drugs, therapeutic medicines and vaccines.

These replica organ systems were first pioneered for human drug toxicity assessments, but are now being developed for use in cancer, radiation, chemical exposure and infectious disease research.

In this blog post, we’ll explore how the science is being developed and successfully used to protect human health.

How it works

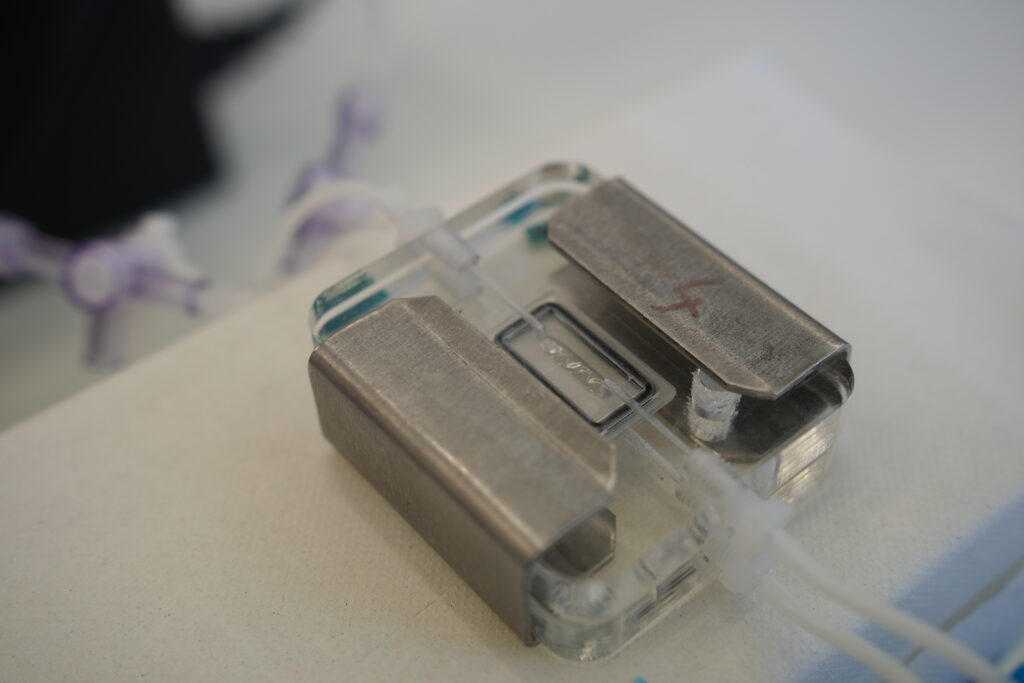

Sometimes referred to as ‘organs on a chip’, but more accurately described as microphysiological systems (MPS), each matchbox-sized cassette contains a small chamber where the function of an individual human organ is replicated on a miniature scale.

Very thin layers of human cells, taken from biopsies or donations, are grown inside the small clear chamber of each cassette.

Once grown, the MPS can be infected with all types of dangerous diseases, to see how human organs respond to an infection. More complicated systems can be built by connecting cassettes with different types of organs, to mirror the internal workings of the body and understand how a pathogen might move from one organ to another.

Where appropriate, cassettes growing gut, lung or airway cells are cultivated in an atmosphere that replicates the push and pull forces and stresses of the microenvironments found within the human body.

Although the systems started by replicating organs, UKHSA scientists are now developing the ability to focus in on protective mechanisms of the human immune system. This will allow a better understanding of how specific immune cell responses fight infectious disease, and how we can enhance or supplement that protection.

3D organs

Outside of MPS, cells from organs have been grown on conventional flat systems, like a petri dish, that do not allow the complex 3D structure of an organ’s surface to be fully replicated.

Some MPS replicate complex surface structures naturally seen in our bodies through integrated pressurised systems which simulate breathing or other normal body movement.

Microscopic observations

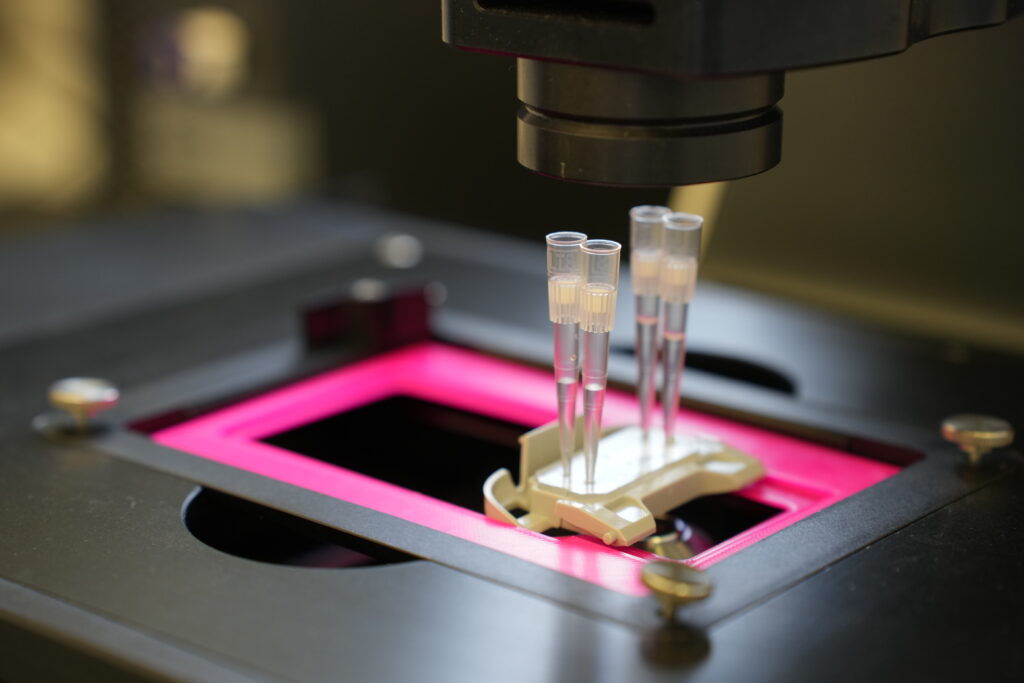

MPS technology also allows our scientists to get incredibly detailed information from tiny samples using complex analytical techniques.

Using these techniques, researchers can perform sophisticated tests on microscopic specimens, including identifying which genes are currently active, examining tissue for signs of disease and conducting detailed genetic analyses by sequencing the entire genome.

These methods mean that scientists can gather rich insights from samples so small they would have been impossible to study just a few years ago.

This allows us to detect small changes in the biochemistry, microbiology and immunology of infected human cells very early on in the infection process, helping us test new ways to protect human life.

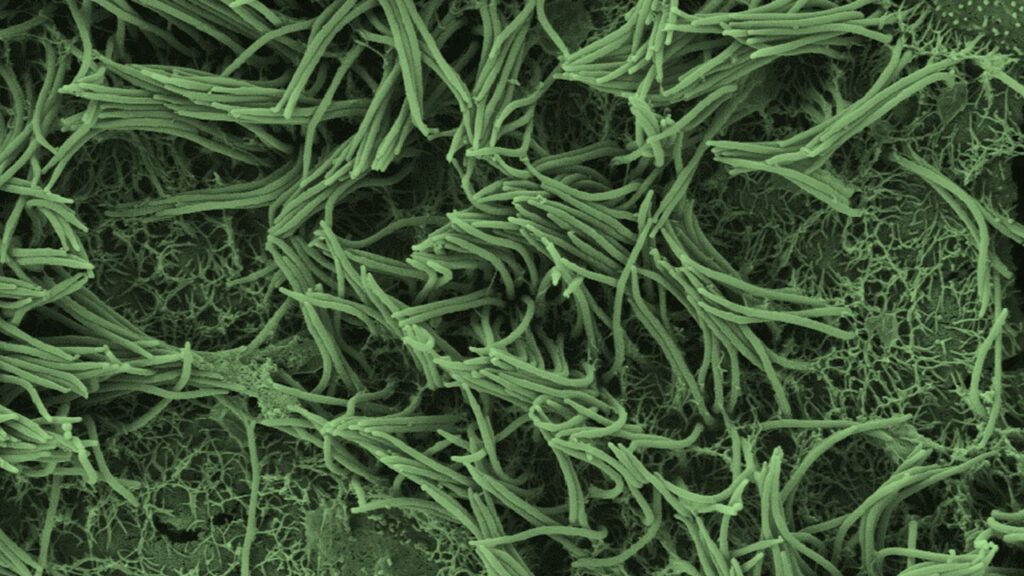

Safety

Our teams work with some of the deadliest diseases on the planet within the strictest, safest, specialised microbiological containment facilities so safety is a priority for all of our work. Miniature MPS systems help us conduct our research studies with complex human models at the highest level of safety.

Our purpose-built high containment labs keep our scientists and the public safe and mean that our labs are uniquely placed to accelerate the development of new vaccines, drugs or therapeutics against diseases of pandemic potential.